Leaving Our Island Day

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. Only two-and-a-half months had passed since the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and fear was rampant. The order gave the Secretary of War (a cabinet position that’s now euphemistically called Secretary of Defense) the power to declare certain areas military zones. One of those zones was a wide ribbon of land running along the entire west coast.

Buried in the wording of the order but obvious to anyone paying attention, was the provision that certain “enemy aliens” could now be “excluded” from this area. And it soon became obvious that the “enemy aliens” tag would come to apply almost exclusively to Japanese Americans.

Because of the sensitive nature of some areas on the west coast and the vulnerability of its shores to Japanese invasion, The US government thought this would be an appropriate action. Japanese Americans might be sympathetic to Japan’s war effort. They might spy. Or commit espionage. They could take photos, send messages, light signal fires.

They look like the enemy, right?

The executive order set the “exclusion” process in motion, and there was little opposition within the government or the press. The fact that two-thirds of the people susceptible to the impact of the order were citizens didn’t matter. The fact that the other third had been in this country legally, most often for decades, didn’t matter either. Although there were really no “enemies” or “aliens” in the population of Japanese Americans, that also didn’t matter.

They look like the enemy, right?

It didn’t take long. By March 30, 227 Japanese Americans from Bainbridge Island, Washington, were lined up on the ferry dock, waiting. They didn’t know where they were going. All they could take was what they could fit into a suitcase or two. They had to sell, or give away, the rest of their belongings, their homes, their farms, their crops, their animals, their pets. Or entrust them to a neighbor for safekeeping. For how long? Nobody knew. They were the first, the first of 120,000 from Washington, Oregon, and California.

Armed soldiers eyed them. The soldiers would accompany them on the ferry, the train, into the “relocation center.” Manzanar: Heat, dust, cold, wind, isolation, boredom, shame. Later, another train. Minidoka: More of the same.

Homecoming

After the war, more than three years later, they came back. Most of them did, anyway. They were “lucky.” The island was a welcoming place. The majority of its residents were glad to see them. For the most part, their neighbors had taken good care of their homes and belongings. The editor of the Bainbridge Review, Walt Woodward, and his wife Millie, were human rights defenders. They did their best to write what was fair and sympathetic and true about the island’s Japanese Americans, before they left, while they were gone, and after their return.

The “evacuees” settled back in. They got on with their lives. They said little. But gradually the stories came out. Leaders in the community stepped forward. Plans for a memorial began. Eventually two new schools sprang up next to each other on the island. One is named after Walt Woodward. The other bears the name of Sonoji Sakai, a community leader.

The stories flourished. There was a reason to tell them: This can’t happen again. The administrators and teachers and supporters of Sakai Intermediate School fought for a program to bring the internment history into the curriculum. They won.

Spreading the Word

For many years, community members who survived the camps, or often now, their children and grandchildren and educators and friends and authors and others who have experienced or learned or wrote about this history, have come to Sakai on one special day a year to share their knowledge with the students. The event is called “Leaving Our Island Day.” For most of the years since its inception, I’ve had the privilege to attend. I’ve been able to share what I learned during and after the time I was researching and writing the young adult novel Thin Wood Walls, a story about a young boy and his family who are removed from the White River area (now Auburn) south of Seattle and sent to the Tule Lake War Relocation Center.

The Sakai kids are always great. Thoughtful questions, respect for the people who endured the hardships (and their age-in attendance was Sonoji Sakai’s daughter Kay, who was described by the school principal as “ninety-eight years young”). And she is, and not just in spirit.

As always, this year’s event was fun and informative. It was particularly enjoyable because I got to drive and ferry over with my writer friend Kirby Larson, who has written exceptional fictional (but fact-based) stories about kids who experienced or witnessed internment. Also along with us was Kirby’s (and my new) friend Judy Kusakabe, who was born in a place called Camp Harmony. Most of you will recognize it under its current name: The Washington State Fairgrounds. For a short time, the fairgrounds were converted into an assembly center for Japanese Americans on their way to far-off relocation centers. Picture a horse or cattle stall. Picture people living in it.

They look like the enemy, right?

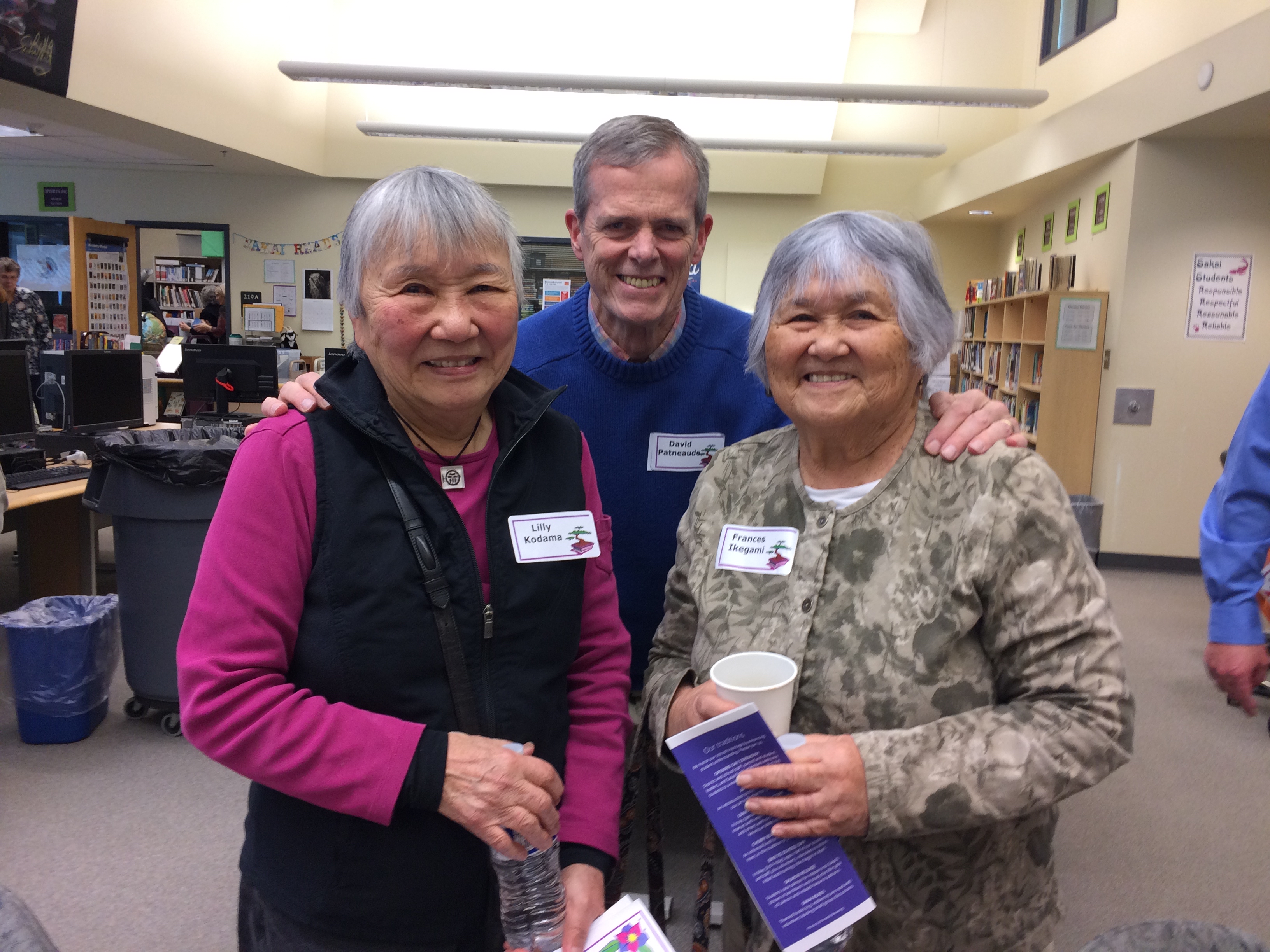

The accompanying photos are of our approach to Bainbridge with the Olympic Mountains in the background; the grounds of Sakai Intermediate; Kirby, Judy, and yours truly outside the school; and my friend Lilly Kitamoto Kodama and her sister Frances Kitamoto Ikegami (and me again) in the school library. Lilly was seven, Frances was five, when Executive Order 9066 came calling.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post

What a lovely write up of that amazing day, Dave. Thanks!